On the face of it, planning for a very long life – well beyond life expectancy – seems like a great way to minimize risk in retirement. Assuming we will have to spread a nest egg out over a long retirement ought to cause us to be conservative and spend less right now. But unless we’re careful with our analysis, the opposite can be true: planning for a long life could lead to increased risk, especially for a surviving spouse.

Most couples fund their retirement expenses from multiple sources, including withdrawals from investment accounts, Social Security income, a pension or two, an annuity, etc. Often, the income available from these sources depends on one spouse being alive. For example, a couple’s combined Social Security changes on the first spouse’s death.1Many pensions cover a single life. Many annuity income streams go away or are reduced on one spouse’s death.

Over the years, we have seen many financial plans that unrealistically project that all non-portfolio income will last until the end of the plan, often well into a couple’s 90s or 100s.2However, if one spouse dies before this extended age (as is more likely than not), the surviving spouse could find themselves with far more risk, or far less income, than they had planned for.

For example, consider a 65-year-old husband and wife who are planning for a 35-year retirement,3until age 100, with the following retirement income sources.4

- Wife’s Social Security: $2,100/month

- Husband’s Social Security: $1,900/month

- Wife’s pension: $1,500/month

- Husband’s annuity: $600/month

- Portfolio withdrawals: $3,000/month from a 60/40 portfolio currently worth $1 million

This couple is expecting $9,100/month in inflation-adjusted income for the next 35 years. It’s worth noting that no couple in history with this plan and these resources would have run out of money over 35 years, as long as both survived the full 35-year period.5

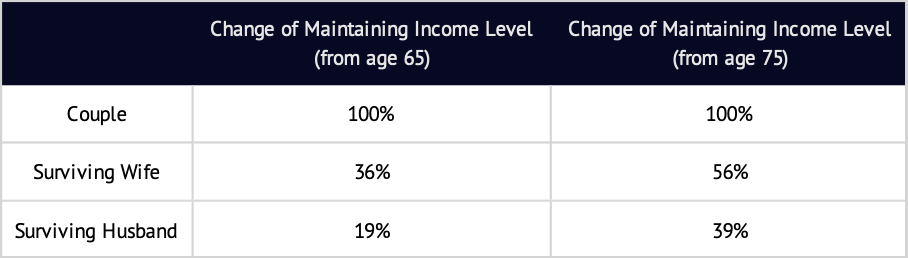

But that’s a big ‘if’. Half of today’s 65-year-old males will die before age 88 (23 years). Half of 65-year-old females will die before age 90 (25 years).6 And historically, only 36% of females and 18% of males in comparable positions could have sustained the planned income level for 35 years on their own.

The longer both spouses survive, the higher the historical chances of maintaining this income level would go. But there is a lot of ground to make up. For example, if this couple made it ten years (to age 75) while maintaining an inflation-adjusted $1 million portfolio, the husband’s chances of maintaining this income level would reach 39% and the wife’s would reach 56%.

Why do we see risk levels shoot up upon one spouse’s death? The reason is that income from Social Security, pensions, and annuities takes a big hit on either spouse’s death. Attempting to make up the difference with portfolio withdrawals could be catastrophic. It would be natural, of course, to adjust the surviving spouse’s income downward, rather than to accept such high levels of risk. But if early planning was flawed, this could mean a big pay cut to the surviving spouse.

When non-portfolio income depends on one person being alive, we need more sophisticated analysis to avoid this problem. We should account for the possibility that one spouse might not make it to the end of the plan and adjust income downward in order to keep a surviving spouse’s risk at a manageable level.

1. A surviving spouse continues receiving the higher of the two spouse’s Social Security income benefit. If a surviving spouse has not reached full retirement age when he or she takes over a deceased spouse’s benefit, this benefit may be reduced.

2. To see whether this is true in the analyses you may be using, check the cash flow ledgers of joint households. If income streams like Social Security appear all the way through the end of the plan, your analysis probably suffers from this problem.

3. Using Society of Actuaries (SOA) Retirement Participant mortality tables (RP-2014 with MP-2017 improvements), there is a 20% chance that at least one member of this couple lives 35 years. Using the same life tables, nine percent of 65-year-old males and 12% of females will live 35 years.

4. We assume each of these cash flows is adjusted for inflation over the full plan.

5. Based on gross returns of S&P 500 stock index, Ibbotson SBBI US Intermediate Term Bond Index, and DMS US Bond Index TR. Indices are not available for direct investment. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

6. Based on SOA mortality tables. Social Security life expectancy is lower: 84 for a 65-year-old male and 86.5 for a female.