The term “Black Swan” has become a shorthand in finance for a large, sudden market drop.1 The dramatic stock market drawdown and economic events of the last month (like the 17 million new claims for unemployment in the last three weeks) have led many to apply the term to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many retirees are worried about whether this Black Swan will require massive lifestyle changes. For businesses that operate with a high amount of leverage and large short-term liabilities, these events can be an existential threat. But evidence from previous Black Swans shows that, historically, they have never had a catastrophic effect on retirement income.

Notable Black Swan Events in History

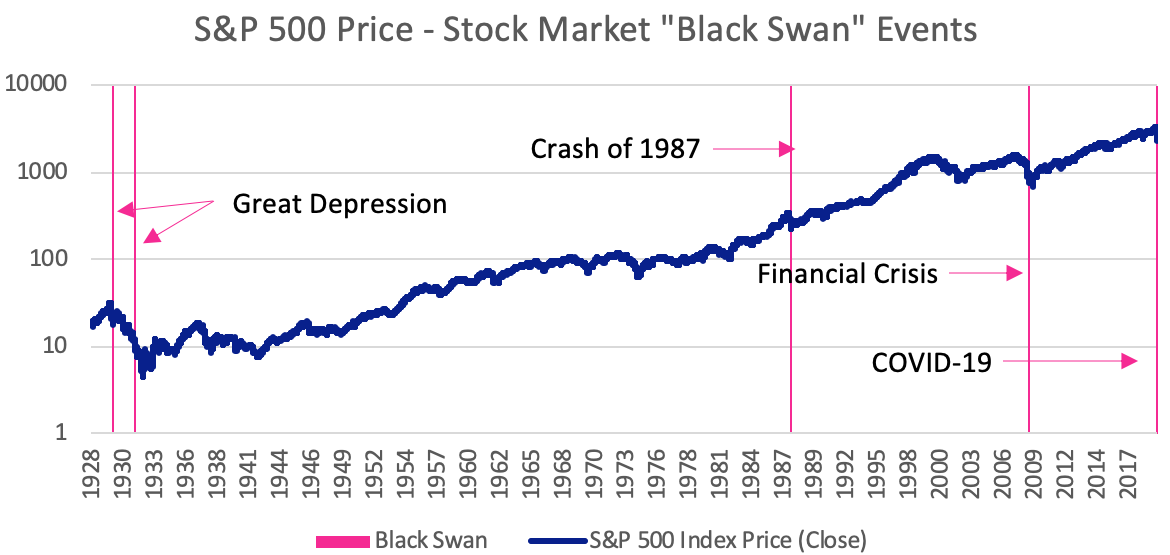

For present purposes, we’ll define a “Black Swan” market event as a US stock market decline of 30% more in a month or less.2 Since 1928, there have been five such events.3

- Great Depression: -42% (Oct-Nov 1929) and -32% (Sep-Oct 1931)

- Crash of 1987: -31% (Oct 1987)

- Great Recession: -30% (Sep-Oct 2008)

- COVID-19 pandemic: -33% (Feb-Mar 2020)

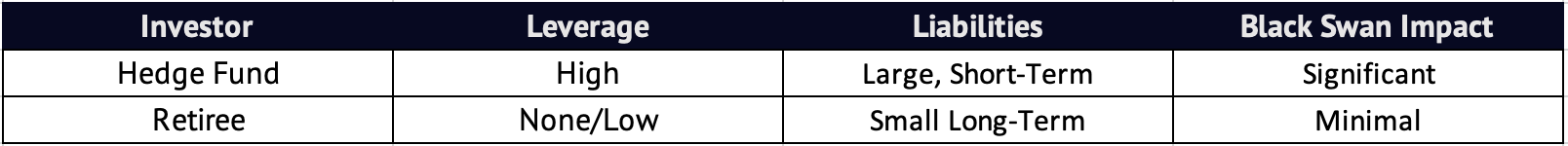

Retirement is Not Like Running a Hedge Fund

Many people are understandably worried about Black Swan events’ impact on their investments. But the immediate financial impact of a Black Swan depends very much on the nature of an investor’s liabilities. Fast, unexpected events with massive market impact have an immediate impact on those with large short-term liabilities. For example, many hedge funds are highly leveraged: they borrow money in order to invest it or use financial instruments with built-in leverage, like futures and derivatives. As a result, a hedge fund’s immediate liabilities can balloon in a Black Swan. Because investment banks reconcile (or “mark to market”) many positions daily, a Black Swan event can have a significant impact on a hedge fund’s ability to stay in business. In fact, events with much smaller drawdowns than those highlighted above, like the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, have caused hedge funds to fold.

But retirees are nothing like hedge funds. The average retiree does not invest heavily in using margin (leverage). Additionally, basic retirement liabilities – namely, monthly living expenses – are each relatively small and are due over a long timeframe.

Additionally, though retirement investment accounts will almost certainly suffer during a Black Swan event, many retirees derive a significant amount of their income from sources like Social Security or similar pension, which is not directly affected by Black Swan markets. That means that a portion of the retirement income that covers core living costs is immune to these market disruptions.

Furthermore, living costs are unlikely to increase significantly for retirees during a Black Swan event. If anything, economic shocks can cause short-term liabilities to go down temporarily as people instinctively pull back on discretionary spending. (This is particularly clear in the COVID-19 pandemic, where stay-at-home orders and social distancing have reduced expenses related to travel, eating out, etc.) As a result, the short-term, extreme impact of a Black Swan event is simply not as large for retirees as it is for some other investors.

Long-Term Effects of Short-Term Swans

Given the large and sudden nature of Black Swans, it is tempting to think that the worst timing for retirement would be immediately before such an event. Imagine this: you begin retirement near the top of a bull market. You’ve planned your spending based on a nest egg that has grown with that bull market. A few months later, the bottom falls out of the market. Sounds catastrophic, right?

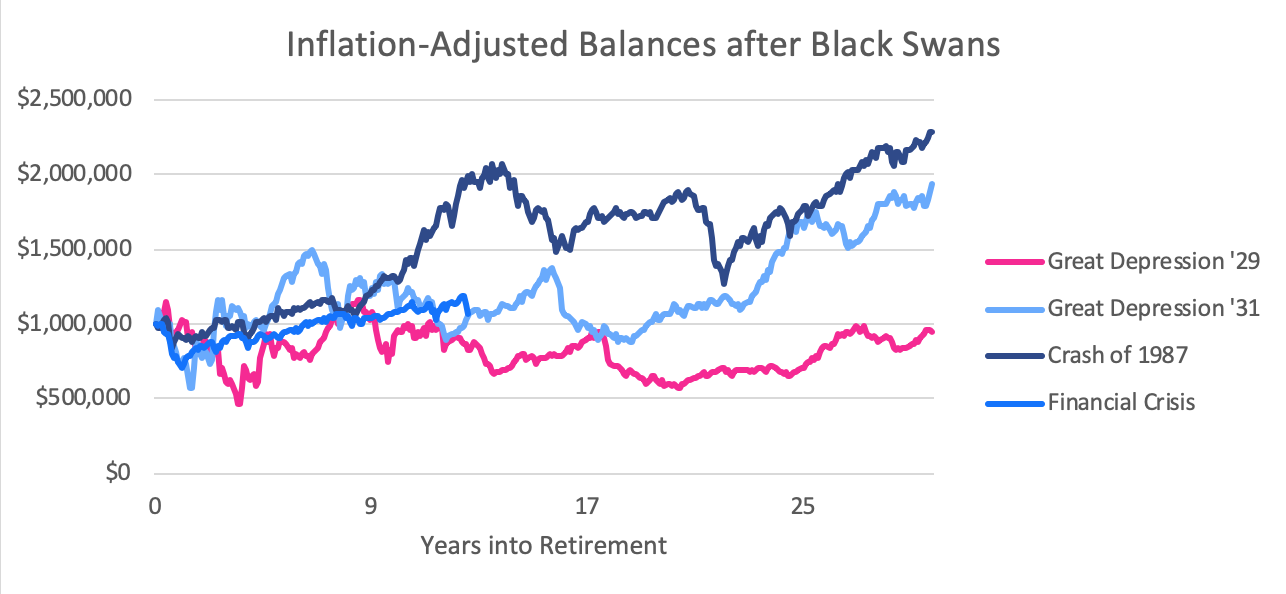

To see how a hypothetical retiree in this position would have fared historically, let’s imagine households with $1 million (in 2020 dollars) in retirement savings, invested 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds, who began retirement six months before each of the Black Swan markets above. Though in real-life retirees’ income should probably change over time based on longevity, economic conditions, and so on, we’ll simplify here and have each hypothetical household spend according to the well-known (though very flawed) “4% rule”. They’ll spend 4% of their initial retirement balance each year, adjusted for inflation.

Below we see how this nest egg fared over time. In the first three historical Black Swan markets, our households would have made it 30+ years into retirement without running out of money. In only one case (1929) would the household have lived through most of this lengthy retirement with less than they had started with. The 1929 case was particularly bad since this household would have had the one-two punch of 1929 and 1931.

We haven’t yet lived through 30 years since the 2008 financial crisis, but so far, this hypothetical household is doing okay. Because the 2008 Black Swan was followed by a longer, deeper market drawdown, it took a while for this household’s balance to recover. But it’s back at a healthy inflation-adjusted level 12 years later. (It’s worth noting that one thing that can cause Black Swan markets to have a lasting impact on retirement is panic selling.)

I wouldn’t wish the returns from these scenarios on anyone, but it’s clear that past Black Swans did not have what it took to destroy retirements. That’s because retirements play out over many years or many decades: plenty of time for fast-moving, brief Black Swans to look small in the rearview mirror.

1. In his books Fooled by Randomness (2001) and The Black Swan: The impact of the highly improbable (2007), Nassim Taleb defines a “Black Swan” as an event that lies outside the realm of regular expectations (like seeing a black swan if all you’ve ever seen were white swans) and carries extreme impact, but that we concoct explanations for after the fact, making it seem explainable and predictable in retrospect.

2. Based on the daily closing price of the S&P 500 Index. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

3. Many events that do not meet this (admittedly arbitrary and restrictive) definition have been called “Black Swans” elsewhere. I have no issues with the broader application of this term. I’ve chosen a narrower definition here in order to focus on the largest, quickest market drawdowns.